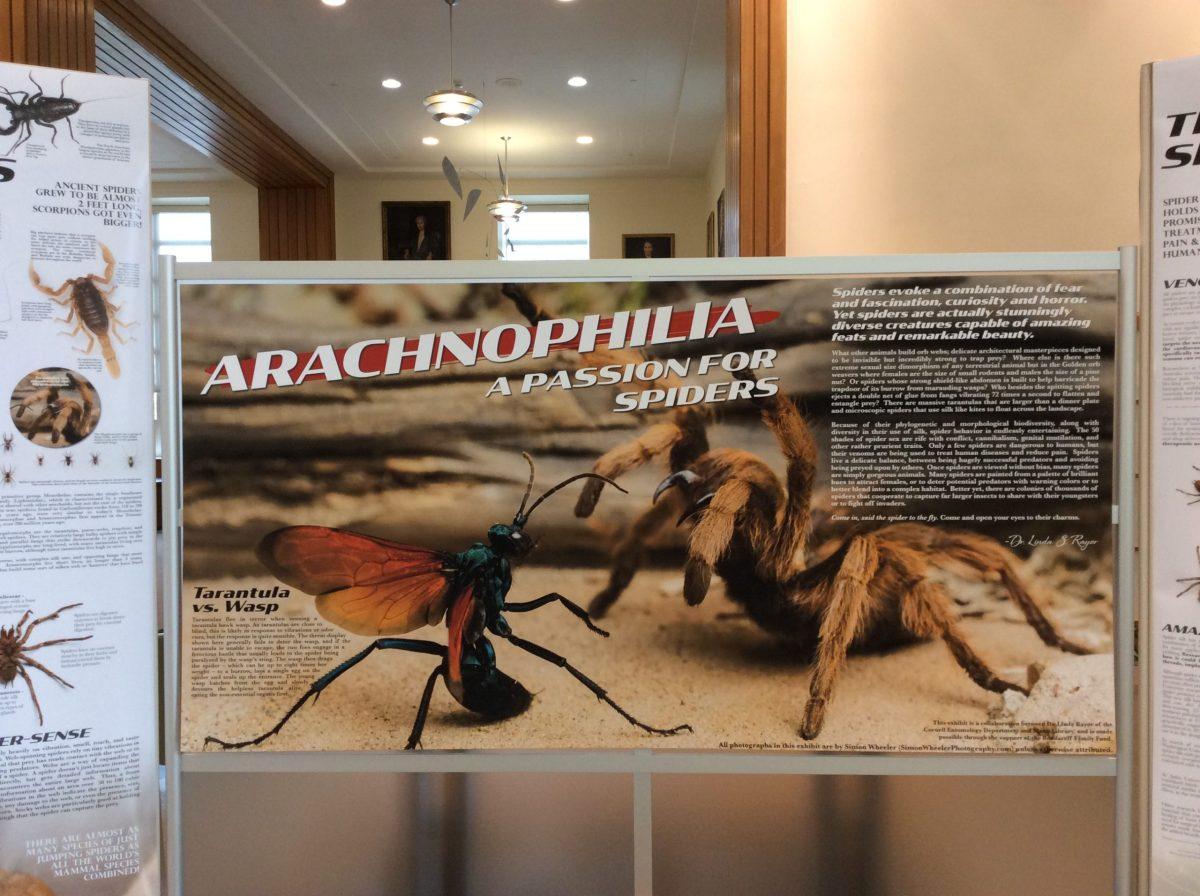

The exhibit is in collaboration with Linda Rayor, Cornell University professor of Entomology, who has had her work displayed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and the Australian Museum in Sydney.

Rayor teamed up with Jenny Leijonhufvud, Gallery & Outreach Spaces Coordinator for the Mann Library, who helped put up all the posters, TVs and displays about spiders.

When the exhibit opened in October, Leijonhufvud estimates there were over a 100 people observing the different spider displays, along with a few live specimens, like tarantulas and huntsman spiders, that Rayor had brought with her.

Leijonhufvud said the response to the exhibit has been better than some had expected.

“There was a little bit of apprehension that people would be freaked out, and that they would not be able to handle so many spiders being on display here, but so far it’s been really positive,” said Leijonhufvud. “People have been interested and learned things they didn’t know before.”

Much of Rayor’s research focused on the socialization of spiders, something Leijonhufvud also discovered by setting up the exhibit.

“It’s interesting to learn about the differences, the fact that you can have such a variety, even within one spider family, like the huntsman spiders. There are lots of solitary spiders among the huntsman family, then there are these social ones that are really different. It’s evolving research to understand how [families] evolves in an otherwise cannibalistic species,” said Leijonhufvud.

The steps involved with displaying the spiders are complicated, and Rayor and her students spent many hours perfecting the process. It involves 40-60 needles and positioning the spiders body, which is then frozen to hold a certain pose, explained Rayor.

After freezing a spider, she said sometimes “once it’s dried, you’re pulling out pins and the bloody legs pop off.”

It takes about two hours to pin each spider, according to Rayor. As you can see in the photo above, this process can sometimes cause a spider’s body to explode.

Key to the process of displaying the spiders is the special chemicals used. Cornell senior Joseph Giulian, who worked with Rayor to display the spiders, said they inject the spiders with alginate and sodium, creating sodium alginate, which freeze dries in such a way as to make the spiders look more life like.

Rayor, who said she has tons of spiders, gave Leijonhufvud information used in the exhibition.

“This is my idea of what’s important for spiders, how they compare to other arachnids, growth and development, spider sex. I have hundreds to thousands of live spiders in my lab because I’m interested in behavior.”

The facts that Rayor consider important include descriptions of their life cycle and how the process of molting works. Spiders can live from a few to 20 years, while molting involves a spider shedding its exoskeleton as its body outgrows the previous shell.

Leijonhufvud said she hopes the exhibit is able to instill in visitors a new-found appreciation for spiders, rather than an innate fear that she thinks society has cultivated.

“So I really hope that some people who come across the exhibit and weren’t expecting it, can get over what might be initially an ‘oh, so many spiders,’ to actually feel comfortable around spiders and to feel that there’s not really a reason to have a lot of fear. That there can be a little more arachnophilia [love of spiders] and less arachnophobia.”