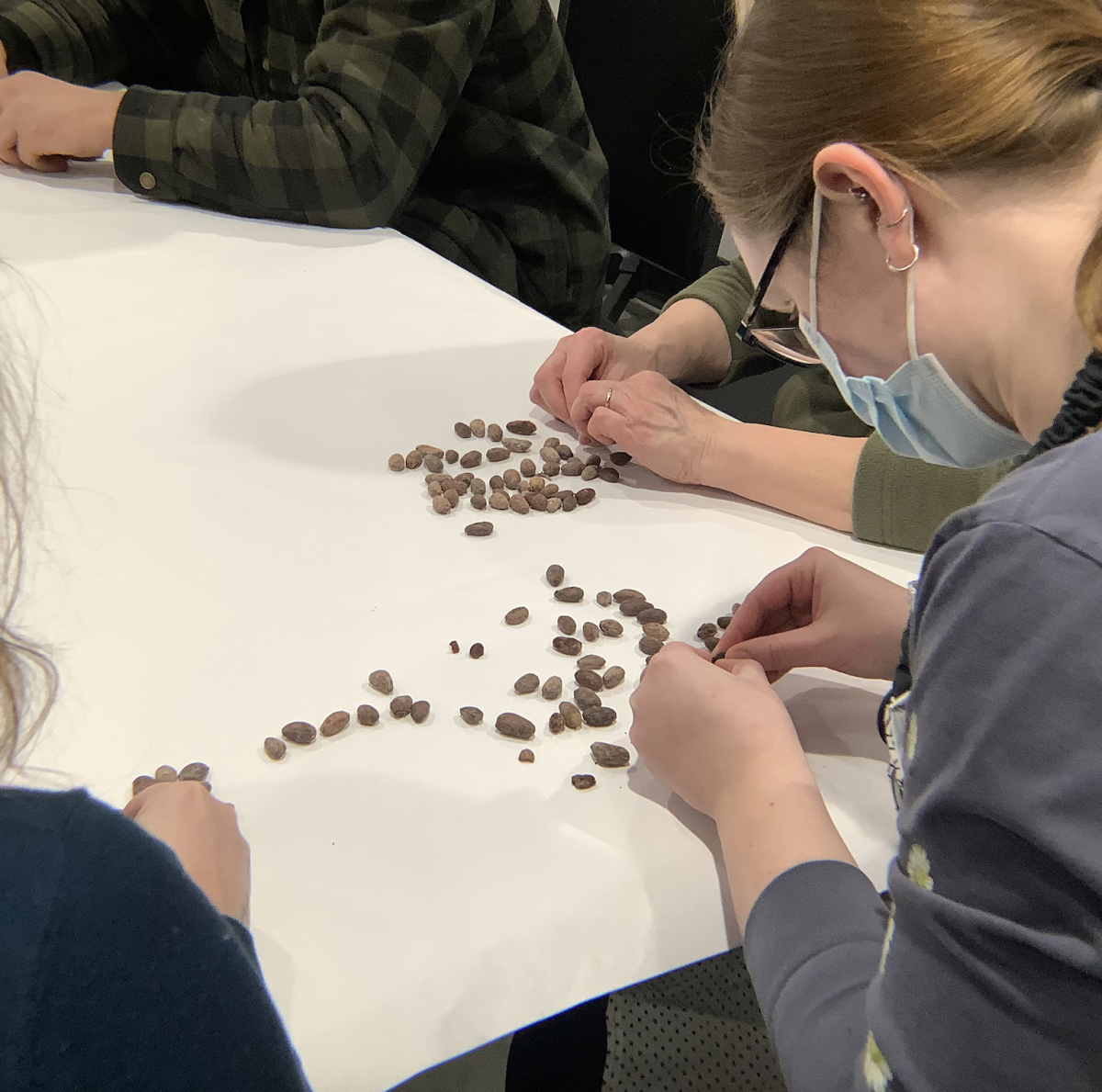

At first glance, historical interpreter Cheyney McKnight’s 19th-century clothing was a familiar sight among performers at the Genesee Country Village and Museum (GCVM). McKnight occasionally wiped her turnip-covered hands on her apron and fanned the flames of an open fire with her ankle-length skirt.

McKnight wore a face mask that tied around her handmade headwrap. Similar to many of the fair’s living historians, McKnight rotated among interacting with eventgoers, enacting her interpretation and tending to her outfit during her performance times.

But her presence at the 41st annual Agricultural Fair — held Oct. 3–4 in Mumford, New York — was distinct from the typical appearance of storytellers at past GCVM events. McKnight is one of the museum’s first Black female interpreters to teach African American history among the group of predominantly white living historians in Western New York.

“People need to hear the words of Black Americans of the past and the present,” McKnight said. “I think that is something shifting right now.”

The Impact of Not Your Momma’s History

McKnight is the owner and content creator of Not Your Momma’s History (NYMH), a program that consults with museums and historical societies to educate audiences about the experiences of African American enslaved people.

NYMH designs its programming to

- Increase the visibility of notable enslaved African Americans whose lives have been erased;

- Introduce local students and their families to Black history that is not normally taught in schools and communities;

- Offer staff training at historic sites about how to accurately represent slavery; and

- Highlight how slavery continues to shape national politics.

McKnight has over 3,000 hours of interpretive experience rooted in historical research, according to the NYMH website. She said she spends considerable amounts of time ensuring that her explanations of slavery are well rounded to disrupt the trend of misinformation surrounding enslavement.

Incorporating New Voices at GCVM

GCVM is New York state’s largest and most comprehensive living history museum. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, its long-standing Agricultural Fair provided community members an outdoors, socially distanced event that emulates what the 1800s harvest season looked like through entertainment, culinary demonstrations and tours.

In light of ongoing Black Lives Matter racial justice protests in the U.S., Kara Calder, senior director of programs, said that it was meaningful to GCVM to host McKnight because her interpretations align with its anti-racism and equity mission.

“Our commitment to telling authentic stories from history and bringing fresh perspectives to how we tell them is very important to us,” Calder said. “In the last few years, [because of] our focus on diversity and inclusion … we made a concerted effort to bring in guest interpreters.”

Calder said that GCVM recently hosted a Frederick Douglass living historian from Rochester, New York, as part of its efforts to center underrepresented voices in its educational programming.

“It is impossible to talk about slavery and the history of African Americans in this country without talking about Black Lives Matter,” McKnight said.

Even in a rural, conservative region like Livingston County, audiences were receptive to NYMH.

“I feel like it’s really nice seeing people with different backgrounds and different cultures,” said Cindy Samper, a Rochester resident from Mexico, who visited McKnight’s site at the fair. “It’s pretty amazing. I really liked it.”

Forging Relationships Through Meals and Messages

McKnight said her method is to lure in visitors with her meals based on traditional recipes, including mashed potatoes and bacon-filled cornbread, and encourage them to stay for stories of Black historical experiences.

“Making the connection between freed slave women and the food that was important in their lives might be a story that [eventgoers] would never be exposed to, so we’re hoping they’ll come away with that,” Calder said.

At GCVM, McKnight shared the experiences of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, two African American leaders with ties to Western New York.

“I decided that I was going to use my body, use my interpretation to really make those connections,” McKnight said. “It makes me feel very powerful to do that — I can tell the stories of my ancestors.”