What does Feminism mean to you?

This is a question that is often asked in schools, in the media and in conversations with young girls and adult women. It’s a question that carries a lot of weight for some people and for others it’s a throw-away term. The word feminism bears a host of definitions that take on many different shapes and sizes throughout not only our country, but the world.

How would you define the term? According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the term means, “the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes.”

What does Feminism teaching look like in schools?

For most schools across the country, feminism is narrowly taught in grade school — oftentimes in American history courses in the context of the suffrage movement and the nineteenth amendment. This is considered not only the first wave of feminism, but also a very white-washed and westernized version of it in the United States.

Bronwen Exter, humanities teacher at Lehman Alternative Community School, said this teaching fails to recognize the racism, patriarchy and injustices that were at play for women of color during this time.

“So having the conversation of how can we not throw out an examination of the vision and the gains, the fortitude of these movements,” Exter said. “Acknowledging their racism, but not be sexist in the way that we don’t even tell the story.”

@madisonmoore1098 I bet you didn’t know about the influence indigenous women had on the Seneca Falls Convention! #feminism #indigenouspeoples #ICParkSM #fyp

How Feminism is taught in a local alternative school:

Alternative school teachers, like Exter, are at an advantage when it comes to teaching about feminism in a K-12 education because they have the freedom to choose their own curriculum. LACS is exempt from New York State standardized testing so they don’t have to adhere to the curriculum put forth by the New York State Education Department.

Therefore, semester long courses like Exter’s Global Feminisms class are available. She says she tries to center the voices of women of color in her course material choices. Students read from women of color feminist thinkers and activists such as Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, bell hooks, Julia Alvarez and Maya Angelou.

“I think sometimes those voices are just the most powerful, like the ideas, the theory that kind of explains the world in a way that makes the most sense often comes from women of color,” she said.

Students at LACS are required to participate in a committee during the school year and one option is the Intersectional Feminist Committee. This committee has been around for 15 years and members learn about feminism and participate in service projects within the community. This year junior, Miranda Mangaraj, is leading the group and is the first woman of color to do so. Mangaraj said the group is trying to encourage diversity by discussing how intersectionality impacts women of color and how the group can confront their overall whiteness together (Ithaca Week/Madison Moore).

LACS is a predominately white school with predominantly white teachers, in a predominantly liberal bubble here in Ithaca. However, Exter says it is important for white women to make sure they are bringing in the voices of women of color into their classrooms.

“To not second guess introducing Black women writers being a white woman, like just do it,” she said.

What about in local public schools?

Not all schools have the freedom to make these choices. Due to time constraints and required reading materials put forth by the state, feminist teaching isn’t emphasized as much in traditional public schools.

Boynton Middle School teacher, Cindy Kramer, notes that throughout most of our history, the voices of people of color were silenced and absent by design.

“I have to say 20 years in, it’s still a mission and it’s still a work in progress and it’s still something I continue to pursue,” she said. “To find stories within every unit that can voice to the people of the time. Some of it is what’s available and has been documented.”

Randi Beckmann, a first grade teacher at Belle Sherman Elementary School, agrees with Kramer and says it is the job of educators to recognize this lack of representation and acknowledge it in their teaching.

“So it’s kind of busting up stereotypes, making obvious that which has been quieted by text and history,” she said.

However, these teachers are still finding ways to bring in feminist thought and female voices into their classrooms, even if it’s not a specific lesson on feminism.

“What I’m always doing… is looking for opportunities to make connections to present day, to add more voices to the story of unrepresented groups including women who have been very underrepresented historically in the history curriculum and I think still continue to be,” Kramer said.

How can you incorporate feminist teaching into your classroom?

While these educators recognize they can do more work when it comes to elevating the voices of women of color, they are all taking concrete steps to bring more feminist teaching into their classroom regardless of whether their curriculums tell them to or not.

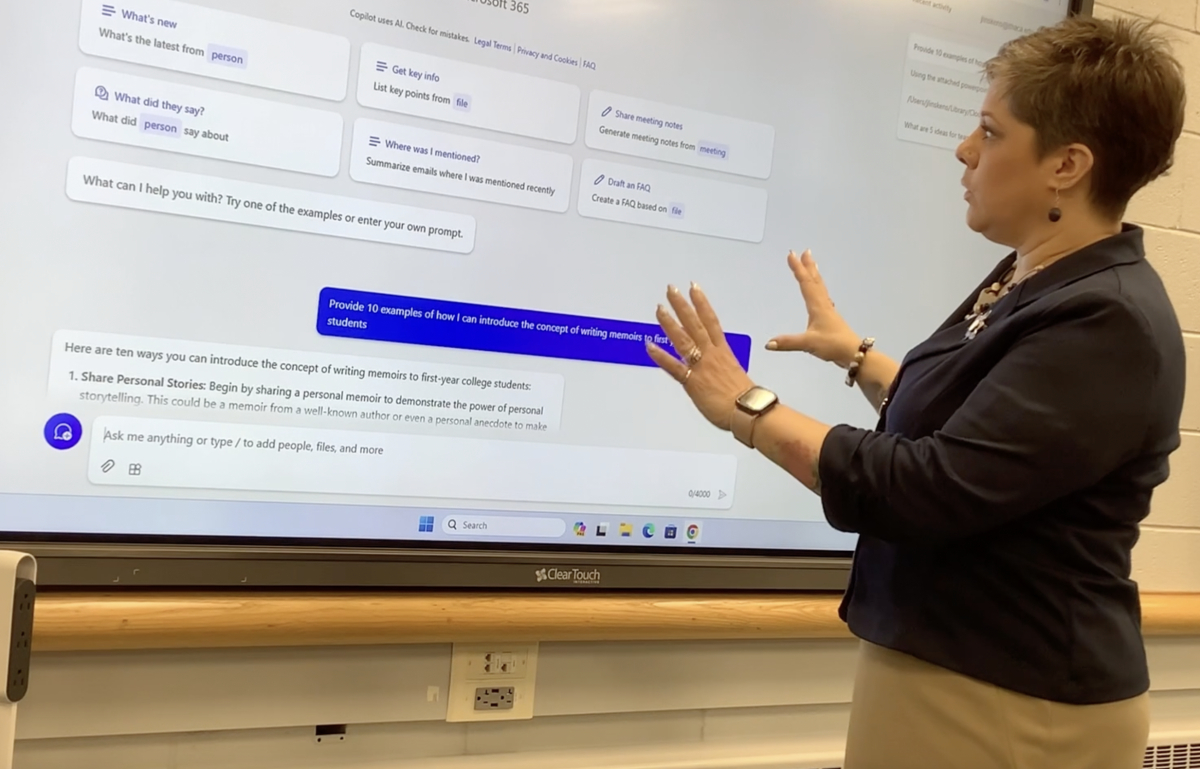

Lexi Hartley, a humanities teacher at LACS said taking simple, small steps in your classroom is a good way to start.

“Just helping students by both building in structures in class discussion that allow all voices to be heard and encouraging students to be mindful of whose voice is in the room and whose voice isn’t in the room,” she said.

And Beckmann urges educators of very young children to not shy away from feminist teaching.

“I would say the biggest thing though is not being afraid to talk about things,” she said. “We’re all so afraid of talking about race and we are so afraid of talking about things and saying the wrong thing and I just feel like we all need to just take that step and that dive and say, ‘I’m going to try it. I’m going to do it and I’ll do my best. If I make a mistake, I make a mistake.’”