Every year, bird-watchers worldwide participate in the Great Backyard Bird Count (GBBC), a project in which citizen scientists report bird sightings on eBird, an app developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

This year’s GBBC ended Feb. 15, but bird stewardship is a year-round job for project leaders at Cornell and local conservationists.

“It’s a really nice, simple, easy, entry-level kind of project,” Becca Rodomsky-Bish, project leader of the GBBC, said. “It’s very attainable for people no matter what your level is in terms of nature appreciation.”

Joining the Count

To participate, citizen scientists can record their sightings with checklists on eBird. Checklists allow birders to catalog the species they see in each bird-watching session, where they look and how long they spend.

The GBBC attracts beginners because it is a low-commitment event. It captures what Rodomsky-Bish called “a snapshot” of where birds across the globe are at one particular time. However, birders can use eBird anytime.

“We know a lot more about broad-scale movement of species with eBird than we ever did before,” Vicens Vila-Coury, president of the Cornell Birding Club, said.

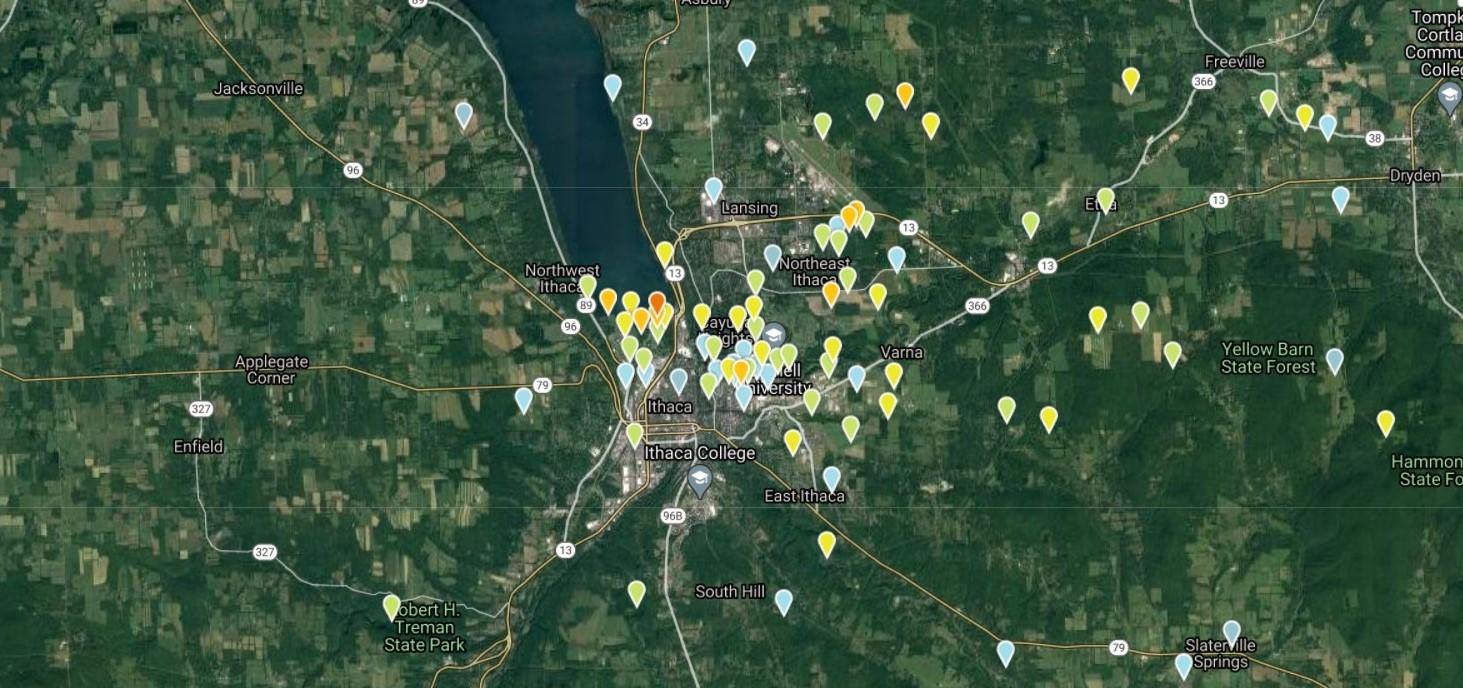

eBird users can also see specific data about bird sightings in their own areas. Here in Tompkins County, data from the GBBC, and eBird in general, is valuable not only to the Ornithology Lab but also to local conservationists.

“When we can get other people involved in something like the Backyard Bird Count, … it gets more people out enjoying the birds and counting them for us and collecting data,” Jody Enck, Chair of the Cayuga Bird Club Conservation Action Committee, said.

The Impact

During this year’s GBBC in Tompkins County, birders observed 95 unique species and completed 889 checklists; 479 hotspots — locations with multiple reported bird sightings — were identified.

Seven species identified in the county during the count are categorized as either “threatened” or “special concern” by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Three of the largest hotspots this year, the Hog Hole wetland at Allan H. Treman State Marine Park, Lighthouse Point Natural Area and Stewart Park, which includes the Renwick Woods, are focal points for the Conservation Action Committee.

As seasonally flooded forests, they are important bird habitats.

“Right now, they’re overrun with a lot of nonnative, invasive plant species, and so we’re trying to take those out and … replant with native shrubs and trees,” Enck said.

He said native plants are more nutritionally beneficial to birds — and the insects many of them eat — than nonnative plants.

Beyond the Count

The committee uses eBird to monitor its project areas. “On any given day of the year, we hope to have somebody out there collecting data for us,” Enck said.

Rodomsky-Bish said the GBBC’s main purpose is to provide a good dataset that scientists across the world can utilize for their own purposes.

“There is no way that even every scientist in the world could capture as much data as we capture in a weekend,” she said. “With a large enough dataset over a long enough time, we can actually do conservation work using that data.”

Scientists can study bird population trends by comparing datasets gathered from the GBBC, other bird counts and eBird over the course of several years.

“It’s a mutual exchange of information,” Vila-Coury said. “The people who developed eBird give birders a way to catalog what they’ve seen, … and in turn, they get a database of all the information eBirders collect.”

For more information about the GBBC, visit birdcount.org.