Mallary Tenore is the author of “Slip,” a book about eating disorder recovery. For her, the subject is personal.

Tenore, a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin, was 11 years old when her mother died of breast cancer.

As an adult, Tenore recognizes the impact her mother’s death had on the onset of her eating disorder.

She said, “I thought it made me special, and I thought it made me feel closer to my mother by staying the same size I was when she was alive.”

Tenore’s pediatrician didn’t recognize the severity of Tenore’s disorder.

“He said it was a passing phase. He told my dad not to worry . . . and so my dad took his advice, and I continued to restrict and to lose weight,” said Tenore.

Delays in intervention

The lack of early intervention led to Tenore’s first hospitalization when she was 12 years old. Her condition required monitoring and stabilization.

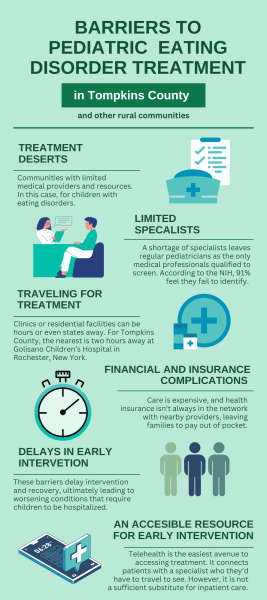

Pediatricians often struggle to identify eating disorders in adolescents, research says. According to published data from 2021 by the National Institutes of Health, 91% of pediatricians and family physicians felt they failed to identify eating disorders.

From 2010 to 2024, there was a “six- to seven-fold” increase in adolescents hospitalized for eating disorders, according to a 2024 Stanford Medical report tracking admission trends across 12 facilities in the United States.

Researchers concluded that misdiagnosis was the leading cause of adolescents requiring immediate high-level treatment, whether that be because of a postponed diagnosis or mistaking symptoms as other illnesses.

While misdiagnosis is part of the cause, eating disorder organizations and recovery advocates say a delay in early intervention and treatment is the reason adolescents are being admitted to hospitals.

This is largely due to barriers to access, especially in rural areas.

Tenore recalls having to travel for hospitalization. Fortunately, she said, she had a resource somewhat close to home.

“I lived in a tiny town, and there weren’t direct resources super close to home, but I did have Boston Children’s Hospital about an hour away. It was close enough where I could go and family could visit me,” she said.

For rural areas with absent intensive inpatient or outpatient programs, the nearest available clinic or residential facility can be hours or even states away because there’s no accessible care. To get to these places, families must be able to afford transportation and time off work.

This can be financially straining, especially on top of treatment prices.

Treatment accessibility in Tompkins County

Upstate New York is primarily rural, and less populated counties, such as Tompkins County, tend to be treatment deserts — communities with limited medical providers and resources.

“If you’re in a rural area, it’s much more challenging to find treatment,” said Casey Tallent, director of the Collegiate and Telehealth Partnership at the Eating Recovery Center, said.

Tompkins County has eating disorder specialists, programs, and groups but they’re for adults. The nearest inpatient center is in Elmira and only accepts patients over 18.

This forces minors to travel more than an hour if they are seeking hands-on treatment, which can create hurdles for the entire family.

The nearest intensive inpatient and hospitalization program to Ithaca for adolescents is at the University of Rochester, School of Nursing and, roughly two hours away.

A shortage of specialists in rural areas leaves regular pediatricians as the only medical professionals qualified to screen for eating disorders. They’re expected to notice signs and properly diagnose, even if their training on the subject is minimal.

Tallent said this puts pediatricians in a challenging spot.

Remote treatment

Telehealth is the easiest avenue to access treatment. It connects patients with a specialist who they would typically have to travel to see.

Mental healthcare “has come a long way with virtual intensive outpatient programs,” Tallent said.

Virtual services spiked in popularity recently because of commuting and pricing. Tallent said the Eating Disorder Recovery Center adopted telehealth services in 2016 “simply to improve access to care” for everyone. However, telehealth is not always a sufficient substitute for inpatient care.

Tenore said it’s important to have in-person services.

“Sometimes you need to be able to actually, physically be in a location, or you want to be,” she said.

Tompkins County and other rural areas within the United States need more accessible treatment for all levels of care, advocates say.

“If you have people who need care, and the care is not available for them, they’re going to die,” Tallent added.

Financial and insurance complications

Receiving care is expensive, and health insurance is not always in network with nearby providers. Tallent said many programs exist in New York, but they don’t take certain insurances.

According to Project HEAL, the majority of outpatient eating disorder providers aren’t in-network with insurances and tend to take only private-pay clients. Prices, on average, can cost $150 a session. Residential treatment is roughly $1,500 a week out of pocket, and $2,000 a day for inpatient or partial hospitalization.

“We often have parents who are trying to get their child [help] and haven’t been able to get the insurance coverage at lower levels of care,” said Stephanie Albers, Project HEAL’s Clinical Assessment Program Manager. “So, while they’ve been plugging along or trying to get help for their adolescent, things have gotten worse.”

Failure to intervene due to transportation or financial reasons only worsens an adolescent’s disorder, overall contributing to the increase in hospital admissions.

Tallent concurred. Despite the restricting circumstances in rural areas, “parents, families and caregivers are doing the best they can with the resources available to them,” she said.

For more information about “Slip: Life in the Middle of Eating Disorder Recovery” by Mallary Tenore log on here.

In New York, for more information on eating disorder recovery log on here.

For general information regarding eating disorder recovery log on here.