Mark Turner farms eight minutes from the town of Skaneateles, New York. His operation has shifted through crops, silage for dairy, a five-year orchard experiment and now a herd of Hereford cattle.

The Turner’s farm has also farmed energy. For years, a 133-foot wind turbine generated 85 kilowatts annually, a landmark visible from Skaneateles Lake. Since 2019, over 300 feet of backyard solar panels have cut $10,000 dollars from his power bills, covering eight months of electricity in his now-retired milking barn.

He calls himself both a farmer and a land steward. A longtime member of the Skaneateles Town Board and the Onondaga Farmland Protection Board, Turner embraces renewable energy in principle but draws a hard line on where it belongs.

“I like solar, but I don’t want them (utility and commercial solar development) in my backyard. They’re being put on good, productive farmland,” he said. “However, I don’t think we have authority to say you can’t do it.”

In farm country, it is only certain types of solar that draw controversy. But it is the thin line between profitability and principle that has divided neighbors over how land changes hands.

In barns, boardrooms and backyard fence lines, the same arguments play out. Solar can cut energy bills, stabilize farm family finances and expand clean power. It can also displace productive soil, alter landscapes and stir resentment between neighbors.

A state on the solar map

New York ranks eighth in the nation for total installed solar capacity. Guillermo Metz, solar and agriculture senior resource educator at Tompkins County Cornell Cooperative Extension, says the state’s growth stems from strong town planning, high energy demand and New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) incentives.

“We’re growing in our energy demand,” Metz said. “We could either continue to replace that demand with gas and nuclear, which is more expensive than solar, or we could do solar and wind.”

Since NYSERDA’s launch in 2011, the state has installed six gigawatts of distributed solar, making it fifth nationwide in residential installations.

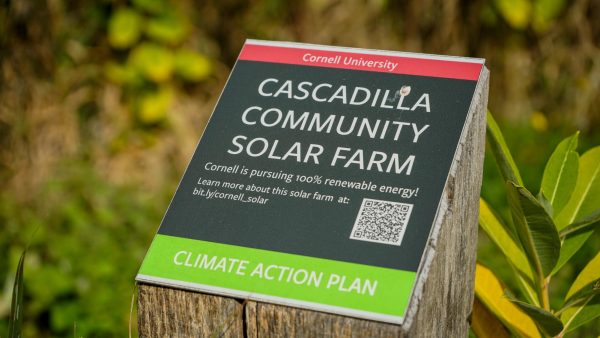

Small-scale projects, under 25 kilowatts, power homes and farms with rooftop or backyard arrays and draw little protest. Commercial projects, like Cornell’s Cascadilla Community Solar Farm, span rooftops or fields and feed into the local grid. But utility-scale solar, the kind requiring hundreds of acres, sparks the fiercest disputes.

“We are losing agricultural land at a pretty alarming rate to development,” Metz said, noting New York lost 364,000 acres in five years, according to the USDA Census of Agriculture.

The reasons for lost farmland are mounting. Owners of marginal farmland must constantly weigh selling against struggling to maintain commodity market profits, loans, lost milk and a struggling farm economy. Then land transitions occur due to aging farmers passing on the operation and generational transfers.

Only a fraction of that loss is directly tied to solar development, despite federal political attempts to victimize themselves against renewable energy. An estimated 8% of New York farmland taken out of production in the past five years was for utility solar, based on calculations by Ithaca Weekly.

Industry estimates it takes five to seven acres to generate one megawatt of solar power. Between 2019 and October 2024, New York added roughly 4,200 MW of capacity, about 21,000 acres. Nationally, 1.25 million acres, or 0.14% of farmland, have been used for solar since 2020, according to the American Farm Bureau.

While solar accounts for less than one-tenth of farmland conversion, low-density residential development is responsible for 78%. “Development tends to happen adjacent to where development already is,” said Metz. “But solar farms defy that.” The American Farmland Trust reports 58% of solar projects have been built on prime farmland.

Mitigation payments require developers of NY-Sun projects in state-certified districts to pay fees based on the percentage of prime farmland. While municipal rulemaking seeks to slow progress, construction continues.

“Decisions ultimately rest with the landowner,” Metz explains. “It becomes an issue of, do you really want to tell your local farmers what they can and can’t do with their land?”

Pressure on farmland

The pressure for valuable farmland north and south of the Finger Lakes is also mounting.

Hudson Egg Farm in Camillus raises 250,000 laying hens and rents 500 acres of cropland to neighbors. That land sits amid expanding pressure from multiple fronts: a Micron factory to the north, Chobani’s planned milk plant in Rome and Fairlife’s beverage facility in Rochester, Monroe County.

“Micron will bring pressure for development of housing and other infrastructure, where on the opposite side of that, Chobani and Fairlife will be building out cowherds for milk production and then also nutrient and manure management,” said Christina Hudson-Kohler, the farm’s egg processing manager.

The Hudson operation also sits near a commercial solar substation run by New York State Electric & Gas. Their flatland has been under steady pressure for development and grid expansion.

“When there’s pressure for solar, a lot of the farmers are calling, ‘Hey, did you get the letter too?’” Hudson-Kohler said. There is a loud conversation about who received letters, but little discussion about decisions.

She notes, “If it wasn’t prime land, you might not want to crop it or have it in ag production.” But she believes there is a good dialogue among farmers in the area to keep farmland as farmland.

Her father, Lee Hudson, co-operator of the farm and a member of the Onondaga Farmland Protection Board, explained how it’s not the idea of farmland being used for anything else than crops rather than the land’ environmental future after solar.

“I don’t think there’s enough money there to clean it all up. And people have told me this…it’s probably going to be one of the largest environmental disasters that people are going to walk away from it.”

Supporting neighbors, strategically

The fall of agribusiness productivity and the sale of farmland often present opportunities for developers.

It’s a common story. “Oh yeah, we get letters all the time, almost one a year. People want land. To build them (housing developments),” Mike Turner said. The timing can be striking. “Somebody just got a forfeiture letter and the next day the developer shows up,” Metz from CCE said.

Near the Hudson Egg Farm, neighbors take varying approaches. “Our neighbor to the east, that’s all been preserved in Farmland Protection, so it’s forever green and they are an organic farm,” said Hudson-Kohler. Another neighbor with 200 acres chose to sell recently. That person wanted to leave his children a financial legacy when they were not directly tied to returning to farming, but he didn’t see farming as viable long-term. Selling farmland for solar would give his family the security he had always wished for.

“You can’t blame a family for being in that position,” she said.

Lee Hudson recalled speaking with that neighbor at a town meeting last year. “Hey, I would like to give you another option. I would be willing to purchase your farm where you could keep a smaller portion of it for your children to pass on, but instead of putting solar on it, would you consider?” The neighbor accepted, and solar was avoided.

“I think it’s just knowing your neighbors or even opening those doors, because if they don’t know what their options are and they think solar is their only option,” said Hudson.

Some farmers find solar solicitations annoying or threatening. But Hudson-Kohler has developed a firm response. “Your project doesn’t align with our values,” she tells developers. “It is a good way to say no thank you, where they are not coming back or even just responding to them. They just appreciate the closure, right?”

The state works to incentivize the use of lower-quality land for development. However, utility-scale and commercial solar projects can still net landowners an estimated 5 to 20% off their energy bill, according to NY Sun Program.

The long process of developing

The process of converting farmland to a solar field begins with a farmer saying, yes. Then come county or municipal approvals. When proposals reach a zoning or planning commission, the details become public and residents question how it will affect them. No federal or state legislation directly restricts housing development or solar on farmland. A switch can occur without a zoning change. Farmland protection agreements and conservation properties have still been sold for development.

But even when there’s an opportunity to use “bad farmland” for solar, administrative burdens arise. Turner has land with shallow soil and shale beneath it. Yet the land is under a conservation easement from the city of Syracuse that forbids construction of buildings.

The irony frustrates him. Syracuse itself wants more electric power but shows no interest in making such farmland available.

Turner knows the sting of being pushed out. In 2019, he left dairy farming after milk buyers repeatedly rejected his herd for being too small, compounded by labor shortages. His dairy barn now sits idle, and crop farming with his brother has slowed as they’ve aged.

He’s seeking practical ways to use the land. “I know farmers don’t think it’s the right thing to do,” he said—a skepticism that echoes across rural New York.

Yet while some farmers view solar panels warily, others see them as a lifeline. In that divide, farmer against farmer, solar energy has exposed agriculture’s newest and most intense conflict: the battle within.