The Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development have awarded five faculty members at Cornell University a $3 million grant to fund research on the effectiveness of anti-smoking advertisements and warning labels.

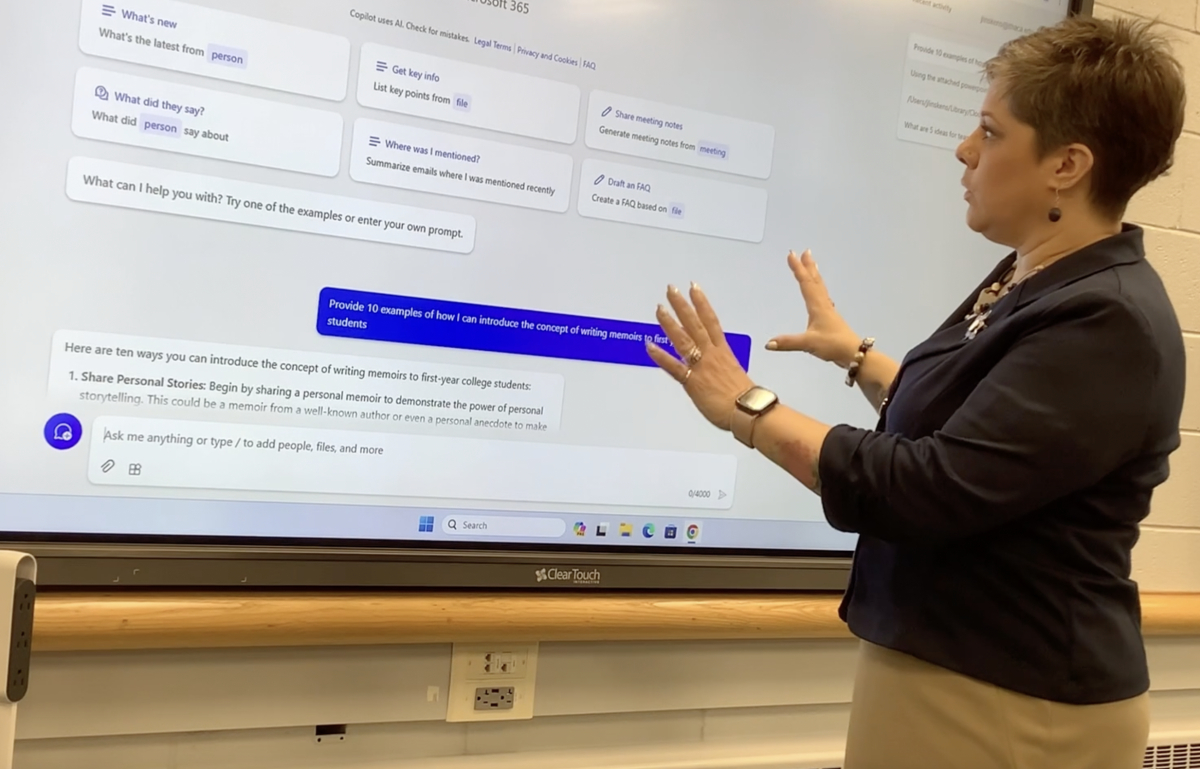

Sahara Byrne, associate professor of communication at Cornell University and principal research investigator, said the grant will fund the purchase of a mobile laboratory equipped with eye-tracking technology to study how people read warning labels, saliva tests to confirm individuals’ smoker status and incentive payments to participants.

“We have been funded to purchase a mobile laboratory, which is kind of like a little tour bus that has the data collection stations inside it,” Byrne said. “We can go into a big city or a community center, park there and invite the participants enter into our lab. In that way, we can hopefully have a better chance of reaching the participants we’re actually concerned about participating in the experiment.”

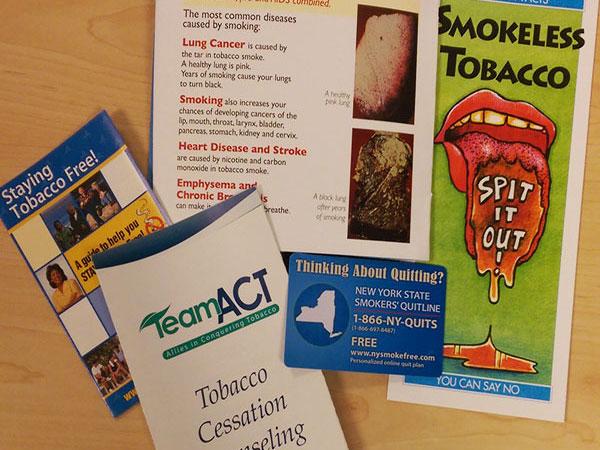

Tobacco use and the negative health effects that come with it are widespread throughout the country, Chris Owens, director of the Tobacco Cessation Center at St. Joseph’s Hospital, said.

“Smoking is certainly a big epidemic that is still affecting a couple million people in New York State alone,” Owens said. “A lot of it is because of tobacco advertising.”

The three major American tobacco companies — Lorillard, Philip Morris USA and R.J. Reynolds — declined to comment on their implementation of tobacco ads and how anti-smoking campaigns affect them. David Howard, senior director of communications for R.J. Reynolds, said, “[I]t is our policy that we do not participate in student projects, or conduct interviews with school or university newspapers.”

Former smoker Amber Davila said that she always noticed the warning labels on the packs of cigarettes she bought, but the warnings were never effective in discouraging her from smoking.

“I know that the boxes of cigarettes that you buy have [warnings] about cancer, and that’s something in the back of your mind, but that’s not what I was thinking about as I was smoking,” Davila said.

The research team will focus its study on lower-income youth populations, who are more at risk of smoking at a young age than youths of other socioeconomic statuses, Byrne said.

“We’ve been interested in this topic for a long time, we just haven’t had access to this particular population,” Byrne said.

Michael Dorf, professor of law at Cornell and a member of the research team, said the legality of anti-smoking warnings is dependent on the verification of their effectiveness.

“A federal appeals court has construed the Constitution to limit the kinds of warnings that may be used to discourage smoking to those that can be proven effective, so showing that some category of warnings is effective is essential to being able to mandate those warnings as a legal matter,” Dorf said.

Davila, 19, said that the anti-smoking advertisements that relied on scare tactics or testimonials by former smokers with serious health problems did not affect her because she did not identify with people who had smoked so heavily for so long.

“I feel like if there was an advertisement more about the social aspect and the peer pressure to fit in, which was my experience, that would be a better tactic,” Davila said.