It’s long after dark, and clad in a pair of paint-flecked, Carhartt overalls, Jane Kim has locked eyes with an Atlantic Puffin.

Well, most of it.

It’s the last night of September, and what will become the first rainstorm of October shakes the trees that flank Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology. The lights are dimmed, and the bustle of activity won’t resume until tomorrow. And yet, it’s here, among the quiet, the phantom of a bird glares out from the wall: orange-beaked, its head floating in space, its body, round and stout, is still nothing more than a painted shadow of its shape.

Kim brings her face closer to the wall, dancing a water brush over the bird’s eyes, its beak, the feathered scruff of its neck. Like a mirage, it takes form. She backs away, and the lift she’s standing on — a vertigo-worthy, 30-foot stalk of wobbly metal — sways just a bit. She’s trying to keep it simple.

“The best birds are ones I don’t have to noodle with a lot,” she says. “It’s just like, I know what I need to put down to make the information there. That’s how I felt about the Hornbill.”

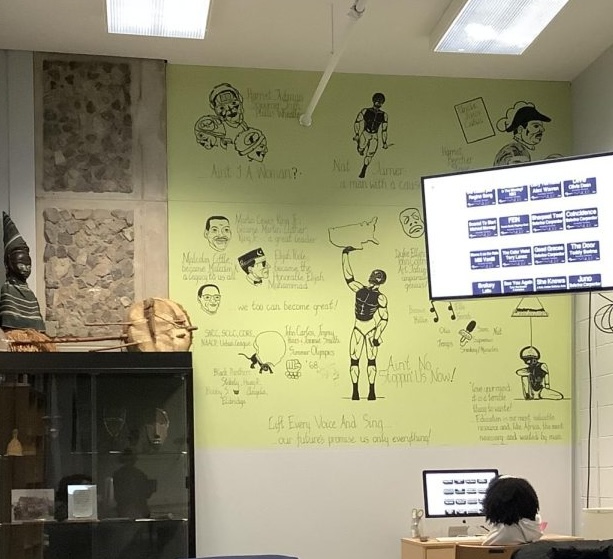

Some feet away, the Hornbill — a long-beaked bird hailing from South East Asia — stares proudly from its one, crimson eye, its bill a boastful orange. It sits among hundreds of others. There’s owls, quetzals and countless more, all adorning a world map that spans an impressive 70- by 40-foot wall in the Lab’s visitor center.

Her husband and business partner, Thayer Walker, looks on from ground level, his shirt patterned with paper cranes, perhaps the only bird Kim will never have to draw.

“Look, it’s an insane project,” he says. “I think we’ve always been — both Jane and I and Fitz and this lab in general .. [are] trying to push the envelope of what’s possible and what’s feasible.”

This is the Wall of Birds, a mural with a daunting responsibility: to chronicle the 375 million-year history of bird evolution, all while representing each and every bird family — of which there are 243 — faithfully. That means each beak, bill, talon and, in some cases, tooth, needs to be life-size and biologically accurate. Further adding to the complexity, all of these illustrations are imposed over a massive map of Earth, ensuring that viewers don’t just know what these birds look like, but also where they hail from.

Safe to say, it’s no small task. Nevertheless, Kim, who boasts a masters in Scientific Illustration from CSU Monterey Bay — and who has experience with vast murals like this one — is taking it head on.

“The director learned that I had done large scale work, and he had always envisioned there being murals in the visitor center ever since the building was created, and honestly, I think he didn’t really find an artist kind of nuts enough to take it on,” she said. “So when I arrived in August of 2014, just remembering my first day walking in was just like, ‘Okay, here we go.’”

That director is John Fitzpatrick, who has served as the Louis Agassiz Fuertes Director for the last 20 years. Throughout his two decades with the lab, Fitzpatrick said the space had begged for some artistic flair. When Kim, a former illustration intern with the lab, expressed interest in doing the mural in 2011, the idea quickly took flight.

“Since we moved into this building in 2003, that wall, which prior to this project had been a pale, drab green color, was literally screaming mural at me,” Fitzpatrick said. “So one day I asked her to stand out there with me and look at the wall and I said, ‘I’ve been dying to have a really good idea for a mural on avian evolution.’ … And she said, ‘I want to do it!’”

Now, about a year into the painting process, what was once a space begging for some artistic addition is now on the final stretch toward completion, slated for sometime in December. At a brisk rate of about one bird a day, Kim has quite literally trekked across the globe. Some birds, like the colossal, trunk-legged Elephant Bird of Madagascar are rendered without color — an indicator of their extinct status. It’s a level of detail that is hard to grasp, Walker said. One that demands a moment, in person, to appreciate.

“Just seeing the scale of this thing is so mind-blowing,” Walker said. “It’s impossible: you tell people it’s a 70-foot by 40-foot mural depicting the 375 million-year evolution of birds, and people think, ‘Wow that’s really big.’ But you can’t understand the scale of it even through photos, without actually coming to see it.”

All the while, Kim has shared photos of her progress via her studio, Ink Dwell, which she and Walker founded in 2011. Driven by the studio’s philosophy of “inspiring people to love and protect the Earth one work of art at a time,” Kim has crafted murals throughout the United States, the grand majority of them showcasing the wonders of the natural world. It’s this connection between artistry and the natural world that, she said, drives her in her craft.

“I love painting, or relaying, a story or information about biology, about science, something that can be engaging and help people connect to the natural world through art,” Kim said. “That’s kind of my favorite thing about what I do — being able to help connect and foster a relationship with nature.”

By 8:30 p.m., Kim’s puffin is finding the rest of its body. It’s only a small piece of what remains — this history will stretch all the way back, to birds’ very earliest ancestors. Kim, however, is relaxed, collected. She’s made it this far, and while she said she is excited to see the mural finished, she won’t be popping any bottles of champagne in celebration.

Fitzpatrick, however, is quick to praise what Kim has done — her “masterpiece,” he fondly calls it, is just as it should be.

“It’s hard to describe,” he said. “How do you describe walking by a dream that’s come true?”