The 21 bells of Cornell University’s Jennie McGraw Tower produce three shows a day almost every day of the year. If visitors can manage the 161-step climb to the top of the 173-foot tower, they can witness any of these concerts, played by Cornell’s chimes masters.

The clocktower itself has seen major changes throughout the years, as has the Cornell Chimes program.

History of the bells

According to documents from the Cornell University Archives and The History Center of Tompkins Center, the original chimes were a set of nine bells donated to the school by Jennie McGraw, the daughter of one of Cornell’s first trustees, John McGraw. The bells, played at the university’s opening ceremonies Oct. 7, 1868, hung in a temporary wooden tower.

In 1891, the bells found their permanent home in the Library Tower (renamed Jennie McGraw Tower in 1961). More bells were added over the years, expanding the musicality of the chimes. In 1998, Cornell began some very necessary construction and maintenance.

Marisa LaFalce, program coordinator for Cornell Chimes, said that in 1998, the chimes program gained enough momentum and campus interest to allow for a major refurbishment.

McGraw Tower was given a facelift after 107 years of wind and water erosion. The 19 bells were taken out of the tower and refurbished and tuned as a set for the first time in history. Two more bells were added to the chimes, LaFalce said.

“By adding a couple of bells, it meant we can play in keys we couldn’t play before,” she said. “We also were able to play chords that before people may not have been arranging music in because it sounded disharmonious.”

The future of the program

Now, LaFalce said, the goal of the program is to increase musicality by creating “a bigger culture of belonging in terms of the music” it plays.

“This is a [music] library that’s been building since 1868,” she said. “Just like there are books and movies that may have seemed appropriate at a certain time and place, are we sure all of the pieces of music that are in our library are appropriate in 2019?”

Chimes master Linda Li said the chimes council talked about removing the song “Dixie” from the library and the choice wasn’t as simple as it may seem.

“There’s questions of ‘should we take it out?’” she said. “Would it erase it from our history and seem as if we are denying it?”

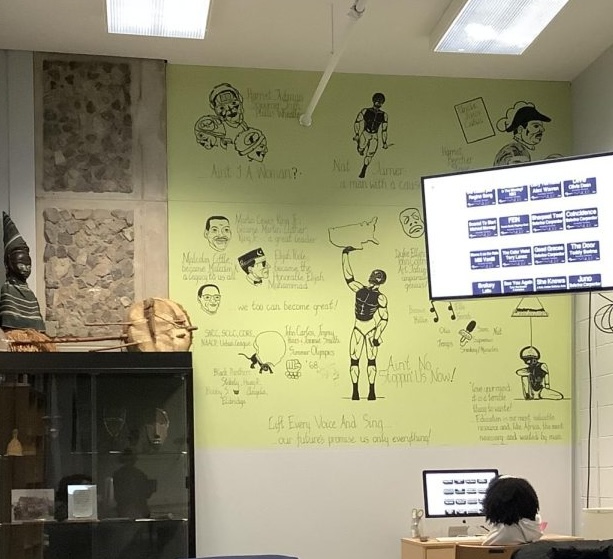

LaFalce also said the program needs to consider the diverse community members of Cornell and what music they identify with.

“We have close to 3,000 pieces in our library, and, as you might imagine, most of it has been written by white men. … That was the major body of people doing that work,” she said. “One area is looking for more women composers and composers of color.”

Li said that if she could add to the library, she’d insert music she grew up listening to.

“What I would add is maybe some Chinese traditional folk songs because there’s only maybe one and a half in there,” Li said. “When I was growing up, I only listened to one Chinese artist. … Her Chinese name is Deng Lijun. … She’s pretty famous in all of Asia and Southeast Asia.”

Li said she thought Lijun would be a good addition to the tower’s collection because she appeals to a demographic that does not see a lot of representation in the chimes’ concerts.

“A lot of students here are from Southeast or East Asia and they would recognize it for sure,” she said. “People would recognize it and feel like, ‘Oh, I’m at home again, except it’s on really big bells.'”