Billions of birds have vanished, according to a study co-authored by Cornell University scientists

The woman sits on a bench and faces a wetland and, further ahead, a wide pond. Using her binoculars, she spots her target: a red-winged blackbird perched on a cattail, who is busy singing its musical trill. She stands, and, with a flash of crimson, the bird is gone.

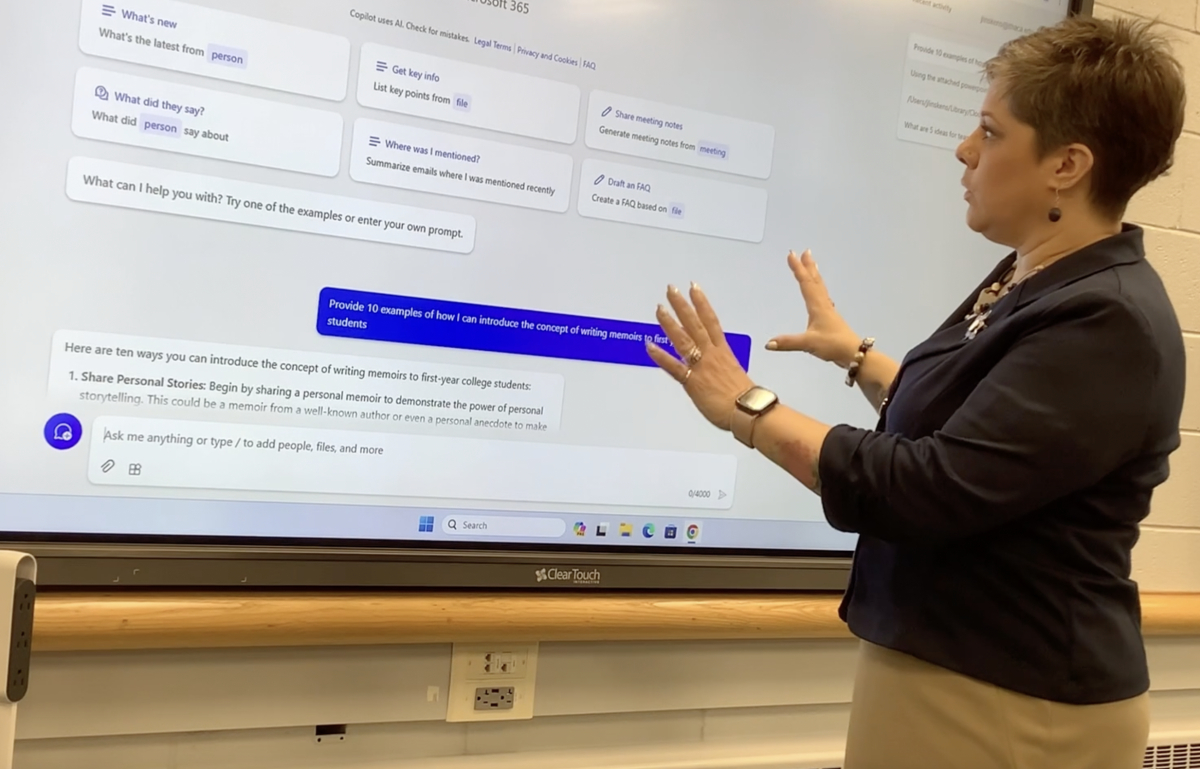

This series of events is familiar to the 45.1 million people that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Survey reported bird-watched in 2016. Nancy Menning, lecturer in the Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College, said people watch birds because they are beautiful and present in everybody’s lives.

“They are accessible to us,” Menning said via email. “They are present in the places we live and it is relatively easy to learn to identify the common birds in our local landscapes.”

But recently, online messaging boards and email listservs for birdwatchers from Tompkins County and nearby counties have been filled with two questions:

“They’re all talking about, ‘Why aren’t I seeing these birds like I used to? Why are these birds gone?’” said Ken Rosenberg, an applied conservation scientist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Among the reduced species are local favorites — meadowlarks, swallows, warblers and blackbirds. These birdwatchers’ eyes aren’t fooling them.

Study shows the decline is real

A recent study co-authored by Rosenberg and other Cornell Lab of Ornithology scientists confirms the decline of certain birds.

The study, which has garnered significant media attention after being published in the journal Science, found the population size of grassland birds have declined 53% since 1970. In fact, bird populations in the United States have diminished as a whole by 29%. That’s a reduction of almost 3 billion birds. More than 90% of the total loss comes from 12 bird families ( including sparrows, warblers, blackbirds and finches).

According to The New York Times, the drop in bird populations is also occurring in other parts of the world, like Europe.

Birds are a reflection of our environment

The study notes that “birds are excellent indicators of environmental health and ecosystem integrity.”

Rosenberg said healthy ecosystems and healthy bird populations go hand-in-hand. He used meadowlarks, which live in open fields, as an example.

“When those birds disappear, it’s an indicator that, that environment can no longer support bird populations,” he said.

The birds can disappear for a number of reasons, he explained, including the use of pesticides, a lack of space or other environmental reasons. Regardless, those reasons hint at a larger issue environmentally.

Taking action

This is not the first time birds have been in dire straits. In the early 1900s, ducks and other wetland creatures were facing massive habitat loss, so bird populations began to decline.

Duck hunters, worried that their prey’s numbers were dwindling, set up the Duck Stamp Act to raise money to protect duck habitats. Approximately 30 years later, Ducks Unlimited, a conservation group consisting of mainly hunters, formed to raise money and protect wetlands.

All of this action has led to population growth — the recent study reported waterfowl as the only biome to have an overall net gain in its population size.

Conservation and funding, Rosenberg said, clearly work. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has created seven simple actions that individuals can do that will have a measurable impact on the birds around them.

“But they’re also things people can take to larger scales,” Rosenberg said. “Ultimately, what we’re really hoping is that people who become more aware, care more, pay more attention and [are] starting to do these actions … will become more of a political force, like the duck, hunters became a voice for conservation.”