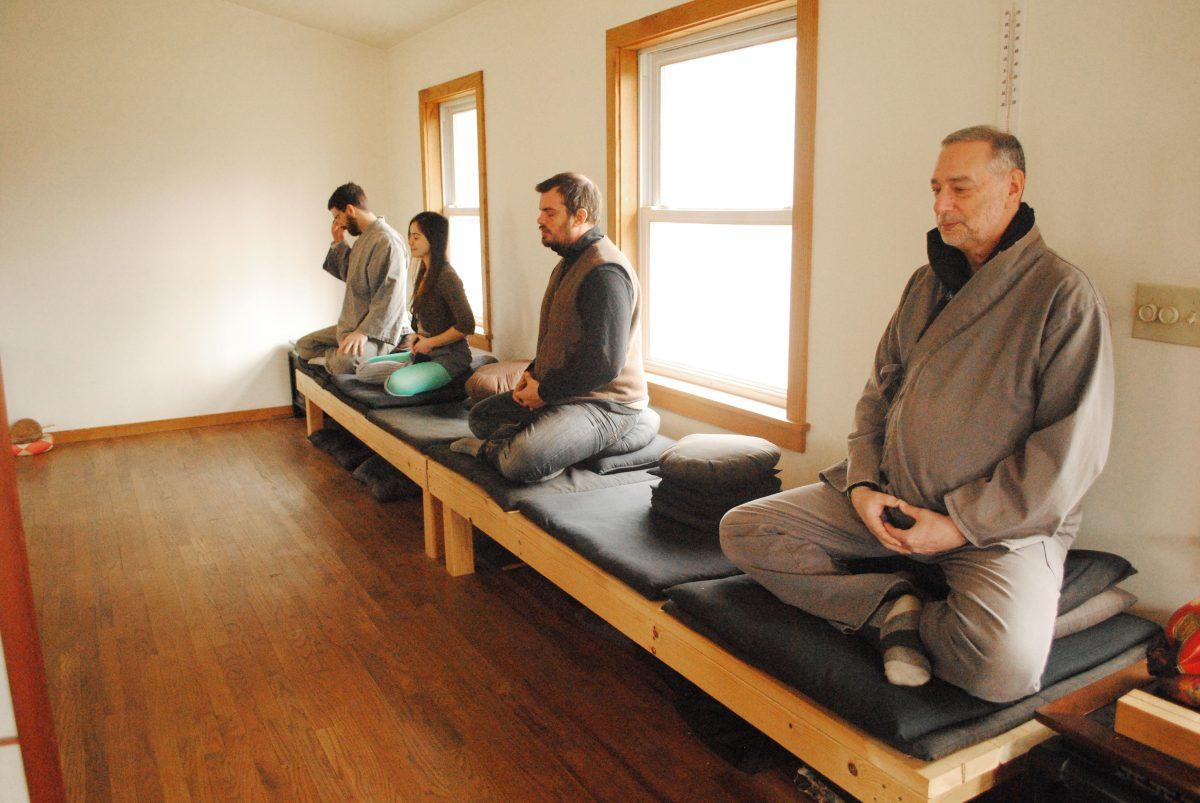

Michael Faber who guides the session, has been practicing meditation for 34 years. He’s a lay monk at the Ithaca Zen Center and the Jewish Chaplain at Ithaca College.

“Every moment of your waking and even your sleeping life, your awareness is 100 percent absorbed in what I call the everyday thinking mind,” Faber said, “Meditation is learning to quiet or calm that mind… in order to create space on the inside so that more insightful awareness can flow in.”

For Faber, the blending of his Jewish identity with Buddhist practices came organically. He knew that he would always remain part of the Jewish faith, but felt that the practice of meditation within the Buddhist tradition was the missing ingredient for his spiritual identity.

A 2008 study conducted by the Pew Research Center shows that 23 percent of the Jewish population meditates weekly. Compared to Buddhism, 61 percent of the population meditates weekly.

“It just seemed to resonate with my own sensibility that this is what makes the most sense to me – that something very simple, direct, uncomplicated and not all bound up with, ‘Oh, you must believe this or you must believe that’ – that’s what most attracted me to it,” Faber said.

In 2013, less than one percent of the U.S. population is Buddhist, according to the CIA World Factbook. Among them, nearly one-fifth are also Jewish, according to Sara Yoheved Rigler, author of Holy Woman.

When practicing Zen Buddhism, Faber said he does not need to adopt Japanese customs and can still keep his own Jewish religious traditions.

Dr. Jane Marie Law, who teaches Japanese Religions at Cornell University, began practicing Buddhism in 1976 in Boulder, Colorado, when Zen Buddhism was at its height there.

Law observes Jewish rituals, but was attracted to two of Buddhism’s main components: the interrelationship between wisdom and compassion, and developing the ability to be present in the moment.

“One of the most powerful lessons you can teach yourself is this method of being present in your life,” Law said, “Your life is the only thing you’ve got, and you can either be here for it or not be here for it.”

Law also deeply appreciates the Jewish religion’s commitment to social engagement in issues of justice.

“I think it’s very important in Judaism that we have this view, it’s called ‘tikkun olam’ or ‘to heal the world,’ and you have to be involved in trying to heal the world,” Law said, “I think its another version of the idea of compassion (in Buddhism), and although they’re very different ideas, at the same time I think they complement each other nicely.”

For Law, conflicts do not need to arise when considering how to balance Judaism and Buddhism.

“We make this assumption that religion always requires that people make an either-or choice, and most people don’t,” Law said.

She says that people live with multiple systems of meaning and do not necessarily believe in everything. People live with different understandings of the world and they overlap.

“Humanity for the first time has an opportunity to blend – and that doesn’t mean the disappearance of distinctive cultures,” Faber said, “It just means that cultures are interacting with each other in ways that are informing each other and that they’re infusing other cultures with the best of what they have to offer.”