In a study published online Feb. 2 in Nature Chemical Biology, Julius Lucks, assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, and his team of graduate and undergraduate researchers, describe how they genetically engineered tiny ribonucleic acids (RNA) that can kick-start genes in the human body.

“These new RNA molecules can now fire up the hard drive,” Lucks said.

What he means is that if DNA is the body’s hard drive, then RNA are the circuits, and his team has built a switch to turn on those circuits. For example, the “on” switch could be used to turn on a gene that would release healthy bacteria, Lucks said, which would help someone better digest food.

“The vision that he had for it, it was just hard not to kind of jump on that dream,” James Chappell, the postdoctoral associate who co-authored the study, said. “It’s very exciting.”

The “on” switches, which have been nicknamed STARS—an acronym for their scientific term—could potentially be repurposed to turn something a different color if they detected a disease. Because the switches are made of RNA, they could be built to detect many of the world’s deadliest viruses—like HIV and even the flu—which are also made of RNA. For example, if the switch was put in a piece of paper, it could change the paper’s color if it touched a drop of blood positive for a disease. The same process was recently used to detect Ebola, using another variation of the RNA switch that acts in a different way.

“I don’t know if our molecule would be able to treat the disease,” Lucks said. “It might be able to detect the disease. But, certainly the knowledge of the fact that RNA can now do this thing would make you want to revisit your understanding of a lot of biology.”

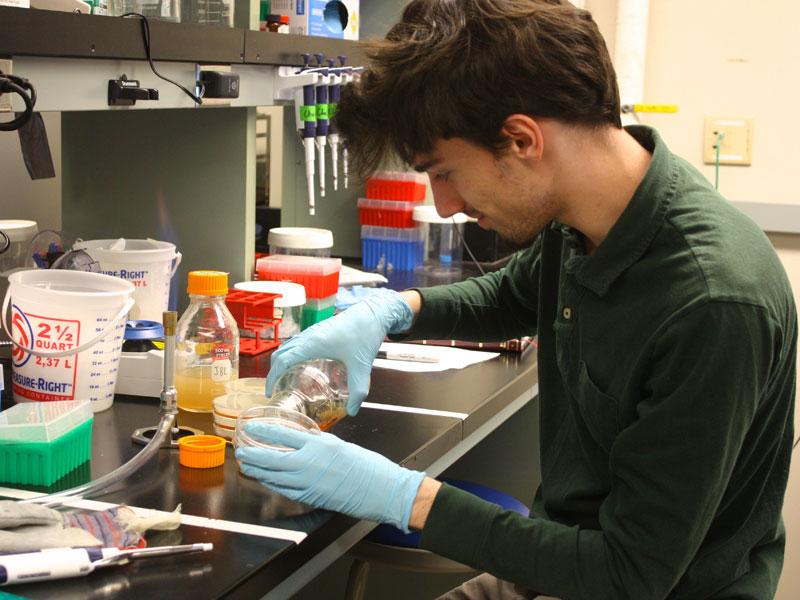

Roughly a year and a half was spent developing and proving the genetic switch would work. Starting with a genetic repressor—or “off” switch, the team found a way to convert it into an “on” switch. Instead of shutting genes off, the invention makes them express themselves.

“I did one strategy and James did one strategy,” Melissa Takahashi, a graduate student and second co-author of the study, said. “The one that James did ended up being much simpler so most of the paper is about that one.”

Cornell’s Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering praised the findings of the more than 20 researchers who worked on building the RNA switch as a leap forward in genetic research.

“It defines an elegant path towards creation of regulatory circuits that facilitate sophisticated engineering and control of the molecular processes that govern biology,” Lynden Archer, chair of the department, said.

The National Science Foundation and Office of Naval Researchers were among the study’s supporters. Several new research organizations have contacted Lucks to study applications for the genetic switch.

“We’ve started a number of new collaborations to use this mechanism in all sorts of different ways,” Lucks said.

The RNA switch, he said, represents a “hot” area of research, partially because of its simplicity. Nature has evolved beautifully but in complicated ways, Lucks said, because it did not evolve to be understood. The RNA switch was built to be a simple solution from the start.