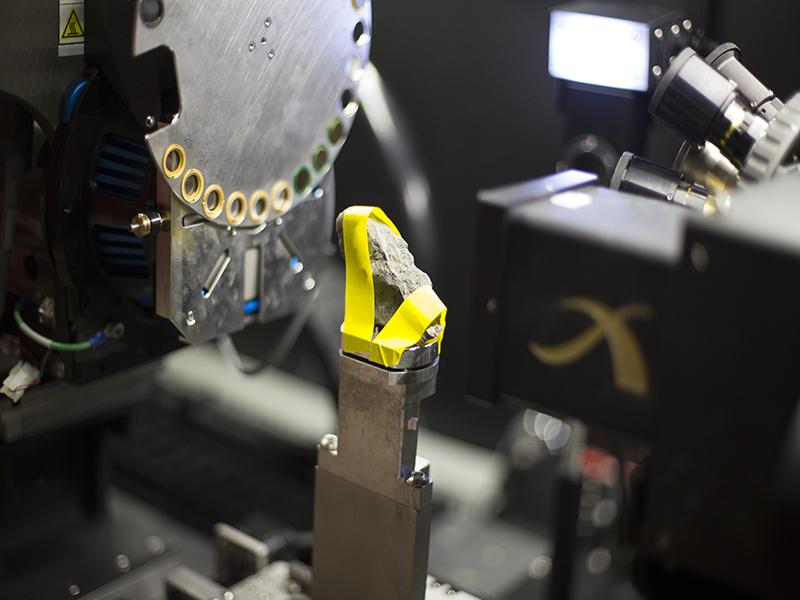

State-of-the-art equipment at Cornell University has allowed researchers to uncover key artifacts from America’s early history.

Mark Riccio, co-director of the Cornell Biotechnology Resource Center’s imaging facilities, was joined by two archaeologists and conservators in April as they tried to unlock secrets hidden within select excavated artifacts. The items date back to the early 1600s, found alongside four graves within the first Anglican church built by English settlers.

“They called me and said, ‘Hey, we have some interesting artifacts of national importance,’” Riccio said. “But they couldn’t tell me what they were.”

What they ended up finding following months of research were human remains, and in the past month, they have discovered keys to identifying who the four graves belonged to:-

– Reverend Robert Hunt

– Sir Ferdinando Wainman

– Captain Gabriel Archer

– William West

Senior Conservator Michael Lavin and Senior Staff Archaeologist David Givens of Jamestown Rediscovery came to Cornell University carrying a sealed silver box and some mysterious silver thread. Jamestown Rediscovery is a foundation aiming to preserve and investigate Jamestown, Virginia, the site of the first permanent English settlement in the U.S.

Lavin said this discovery was huge in the context of the foundation and American history. When they first broke ground in Jamestown in 1994, Lavin said they weren’t even sure remains of a fort or a church were there — they only had historic records.

“When you think about it that way, lost fort found, lost church found, founding fathers found, all of these people were lost to history,” Lavin said. “Mark actually played a large role in helping us identify these founding fathers.”

While the foundation had worked with other x-ray technology in the past, one object proved to be a challenge, Givens said. Their usual x-rays couldn’t penetrate them.

“The machine that we used didn’t have the power to get through one of the lead objects inside, so as we were working through the process of trying to understand — and not just image what’s inside but understand what it was — we knew we had to go up in power,” Givens said.

The machines at Cornell can scan sub-regions in objects as small as 30 centimeters, and produce a clear picture — down to hundreds of nanometers in resolution — of an object’s entire innards. They’re also more safe for delicate items, like fossils and artifacts, because the scanner moves around the stationary object, Riccio said.

The scanning process took about a week, significantly longer than most scans, Riccio said. This was largely due to the number of questions the researchers came with, Lavin said.

“We were getting images … right off the bat, but we would want to know ‘Is the lead object that was in the reliquary, was it hollow, was it mold-made?’” Lavin said. “And he would work with us on the fly to try and answer these questions. It was very unique to have an expert right there, and the equipment, and being able to answer our research questions right then.”

After the scans at Cornell, Lavin and Givens did more scans with Micro Photonics in Pennsylvania and had the data 3-D printed for better observation. The silver box was identified as a reliquary, a Catholic container for relics, and the lead object was an ampulla, which most likely held holy water. The silver thread was from a bullion fringe, which helped the researchers identify the rank of one of the people buried.

Riccio said this technology has allowed the foundation to be able to do things it previously couldn’t, and that this can be applied to fields outside archaeology.

“The future is big. Huge,” Riccio said. “I see this technology playing a role in many facets of our lives, from medicine to commercial products to research to education.”