Samantha Underwood and Matthew Honold, who work at the MacCormick Secure Center in Brooktondale, NY, decided to integrate hip-hop music into their teaching curriculum after multiple requests from their students.

Their students, residents of the MacCormick Center, are juveniles who have been found to have committed acts, which if tried in adult court, would be crimes.

“We started teaching them a standard curriculum. All the same things, but it didn’t really work, it wasn’t really successful,” Underwood said.

Underwood and Honold began asking their students what musical genres they wanted to learn. The majority of residents responded they wanted to learn hip-hop.

“They were all interested in hip-hop. That’s their musical background. That’s their musical knowledge,” Honold said. “And that’s what they wanted to do, so we began using Pro Tools and their favorite instrumentals to record tracks.”

Now, during class, the

residents write original lyrics and record them over instrumentals and beats.

Underwood and Honold’s music class is part of the normal school day for residents of the MacCormick Center, which is one of three maximum-security juvenile justice facilities in state of New York.

“Sometimes, the guys have trouble knowing what they’re feeling and why they’re feeling it,” Underwood said. “This is giving them a way to safely express their emotions and learn to understand and control them. It’s a coping skill.”

Underwood and Honold’s engaging teaching method reflect the core principles of HEARD [Human Expression through Arts: a Resident Development Program], an Ithaca College student organization that the two helped create.

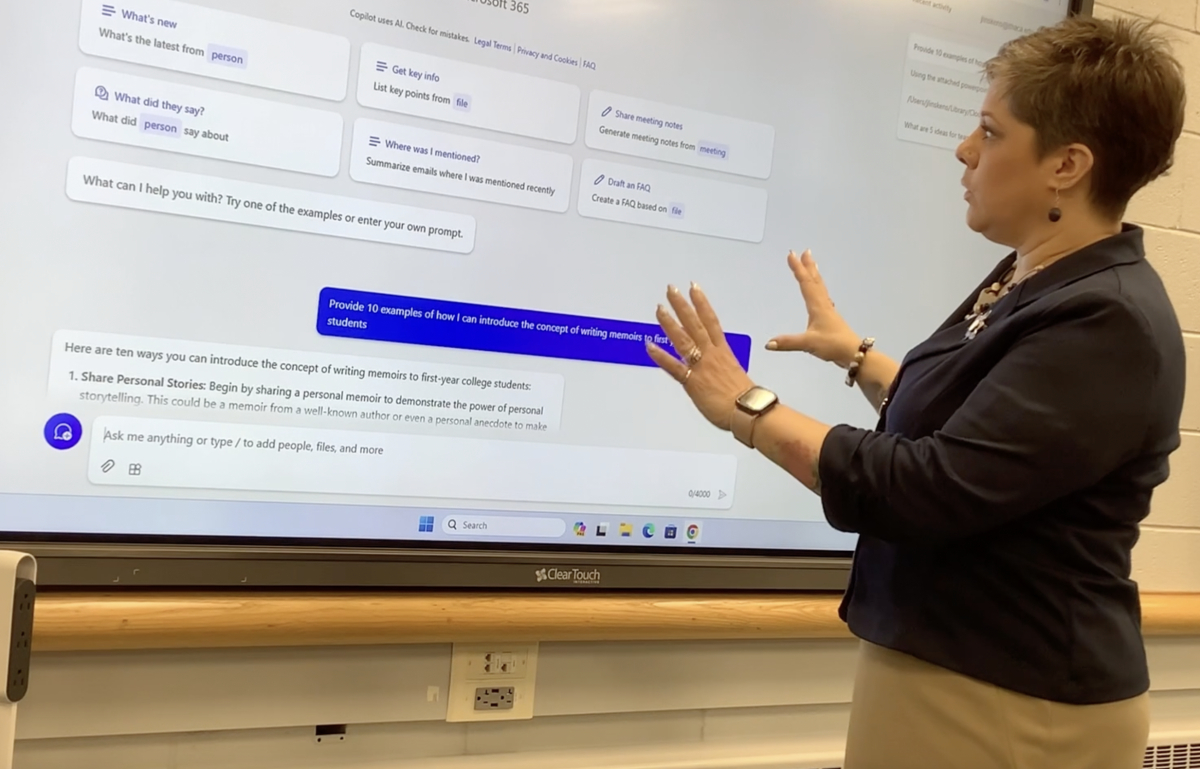

The program began out of a proposal and grant-writing course taught by assistant professor Patricia Spencer and emphasizes a curriculum structure based on student needs.

“The name of the program, ‘HEARD’ came out of a conversation that students had with the residents,” Spencer said. “One resident said, ‘Yeah, they listen, but I don’t feel heard.’ It came from an idea of providing an outlet for them to be heard.”

Spencer works with fellow Ithaca College professor Jessica Barros as mentors to the program.

Barros, whose research focuses on hip-hop language and race, acts as an advisor to HEARD to develop programming aimed at building coping skills through hip-hop.

“You can look at hip-hop culture as a form of therapy, a way of coping because it grew out of that,” Barros said. “Afrika Bambaataa was always clear that it grew out of a movement to replace the gang violence that was emerging in the Bronx.”

Sean Eversley Bradwell, an Ithaca College professor, teaches a class on hip-hop culture that Underwood and Honold are currently taking to supplement their teaching. Bradwell said hip-hop music may be a more culturally appropriate art form, given the primarily African American and Latino racial demographics of the MacCormick Center.

“As crafted and constructed and contrived as those [hip-hop] songs may be,” Bradwell said. “They’re much more relatable in that it’s folks that look like them, talking about what they might have experienced in some form or fashion.”

While contemporary hip-hop music may be more relatable to Underwood and Honold’s students, replicating the often explicit lyrics of mainstream songs can present a problem of appropriateness for residents of juvenile justice facility.

Christopher O’Connell, a vocational specialist at the MacCormick Center, said the integration of hip-hop music into the program’s curriculum presents a unique balancing act for both residents and teachers.

“The appropriateness of what they want to write about doesn’t necessarily jive with what OCFS [New York State Office of Children & Family Services] stands for,” O’Connell said. “So that’s kind of a touchy point to get these guys to be creative enough to talk about their lives, or rap, or whatever, but to do it in an appropriate manner.”

The residents are prohibited from using profanity or explicit references to drugs, sex or violence in their lyrics. Underwood said the challenges of creating appropriate content can also serve as an educational moment.

“They’ve come from the streets, from drugs, many have one or multiple children and they’re not even 21 yet,” Underwood said. “Obviously, they’ve dealt with the things that they want to rap about. So part of me feels like I’m stripping them of their culture, but if we can get them to talk about it in a different way, to be creative about it, then maybe we have an opportunity to teach them about what a metaphor is, what a simile is, what imagery is.”

At the time of publication, the New York State Office of Children and Family Services had not granted Ithaca Week permission to interview residents of the MacCormick Center.