Over her past four years at Ithaca College, senior Emma Grabek has encountered many homeless children in the Ithaca City School District.

She recalled one powerful experience when doing fieldwork in a second-grade classroom at South Hill Elementary School in Ithaca, NY for an education course.

“There was one girl in our class who was homeless,” she said. “She actually ended up leaving halfway through the school year because of her homelessness situation… Basically, Child Protective Services removed her from her living situation and she ended up having to move in with family in Florida.”

Unfortunately, cases such as this second grader’s are not exceptional.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report, as of Nov. 2015, New York had the highest population of any state of homeless families with children.

That number, 52,115, is significantly higher than its runner-up, California, with 22,582. Of course, that number is substantially impacted by New York City with its population of 8.5 million people. However, of homeless families with children that are documented as such, “virtually all were staying in shelters (less than one percent was unsheltered).”

Despite the high rate of sheltering, the number of homeless children in New York State is still increasing. “New York had the largest one-year increase in family homelessness, with 4,168 more people experiencing homelessness as members of families with children, a 9 percent increase between 2014 and 2015,” the report stated.

When it comes to homelessness and housing insecurity, resources are low. The Rescue Mission’s Ithaca location opened in 2013, and provides 10 units for temporary housing for the homeless. Meanwhile, its Syracuse location has 183 beds.

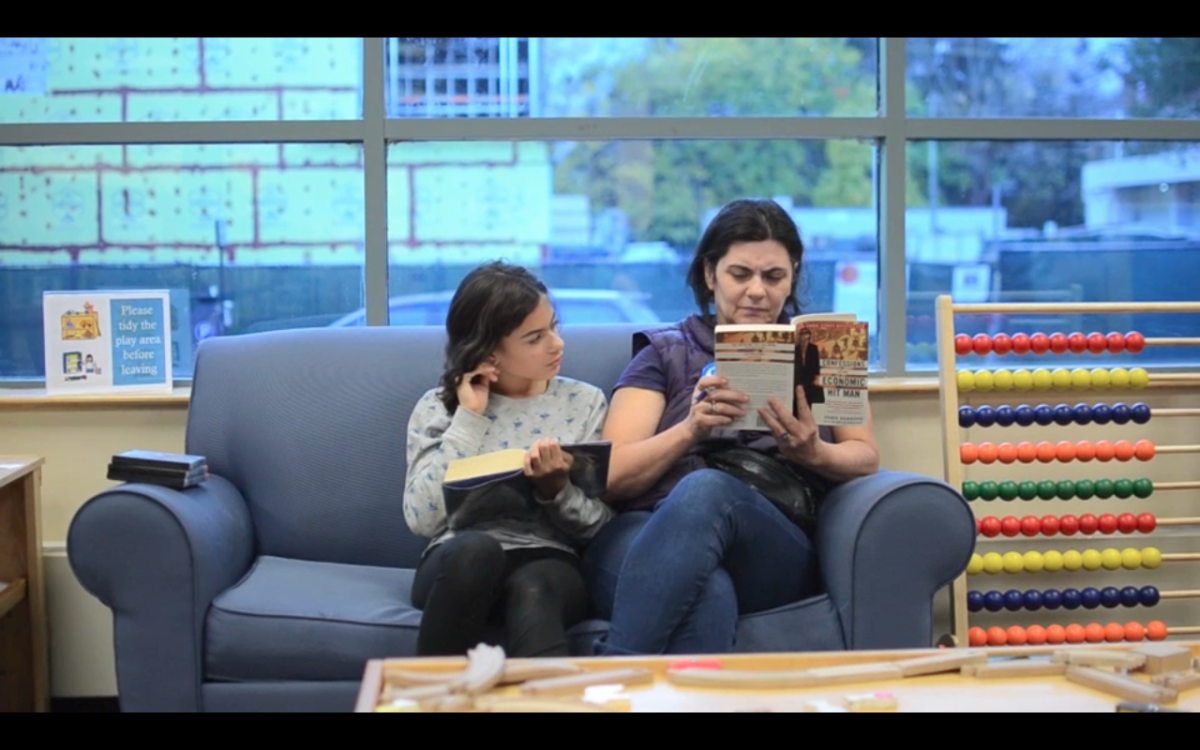

As Nicky Koschmann, Ithaca resident and Ithaca College professor, noted when talking about homeless youth in her Northside neighborhood, it takes a village to provide care for homeless children in Ithaca. Koschmann considers herself a small part of an informal network of parents with children at Beverly J. Martin

Elementary School in downtown Ithaca, cited anecdotally by both Koschmann and Grabek as the school with the highest homeless population.

“We live in an area of Ithaca that has become very gentrified in the last, say, five or 10 years,” Koschmann said. “It used to be an area that had a lot of housing for low-income families, and now the housing is becoming more and more expensive as landlords are realizing they can charge a lot more.”

She said that some families, when pushed out of their housing, temporarily stay in a homeless shelter because their alternative housing options are limited, especially if they don’t have a car with which they could explore Ithaca’s neighboring towns, which are generally more rural and more affordable.

Koschmann emphasized that she does not consider herself an activist for this cause, but has gotten involved by “offering to sometimes open [her] house to have some of the kids stay with [them] for a while until the families get settled,” she said.

Outside her neighborhood, Koschmann has been a part of the community of parents and educators of the children at BJM Elementary School for the past nine years.

“My experience at BJM is that the families really help each other out a lot, and stories get exchanged when there are families in need, that information gets passed in a very respectful way,” she said. “I’ve had psychologists or counselors contact me, ‘This family needs this help. There’s this need. Can you fill it or do you know someone who can?’ That sort of network happens very seamlessly at BJM.”

Melissa Ens and Edna Brown are two social workers at BJM who aid in facilitating those sort of interactions.

“Usually on our caseload, if I have two grades and the other two [social] workers have two grades each, we’re typically dealing with at least one homeless family among our group,” Brown said. “Sometimes we have five or six, up to eight maybe, a year in our school.”

This number is affected by the Advocacy Center’s shelter, which falls in BJM’s catchment area, Brown added. This means that children staying at the shelter with an adult are enrolled in BJM rather than any of the other local elementary schools. The Advocacy Center’s shelter provides temporary safe housing for individuals escaping domestic violence situations.

Ens said that this can negatively impact how certain students perceive school holistically.

“When families don’t have stable housing, they often have to move around a lot, and so their kids move from school to school to school, and so there’s inconsistency with their relationship to school,” she said. “There’s a lot of interruption in education for children and that can be really challenging.”

The Ithaca Voice, a local news outlet, conducted an analysis in winter 2016 that implies that this rate of homelessness is consistent. As founder Jeff Stein reported on Jan. 12, 2016, “An Ithaca Voice analysis shows that Tompkins County has a per capita homeless rate of five times that of Onondaga County, where Syracuse is located.” However, according to Ithaca.com, that report was based on counting homeless individuals on one night per year.

“Despite Ithaca’s relative affluence and prosperity, we actually have a worse homeless problem than some of the other poverty-stricken cities in upstate New York,” Stein added.

Grabek has not just worked with Ithaca’s youth as an education student, but also as a WyldLife leader, which she has been since her freshman year at Ithaca College. WyldLife is a program of Young Life, in which mentors work with middle school students to provide guidance through a Christian-based philosophy. Grabek has worked primarily with students at Boynton Middle School in Ithaca. She said that although the students she works with are not specifically homeless or from low-income families, many students in those populations attend WyldLife programs.

“That is how I met a lot of kids who have experienced poverty or are currently experiencing poverty in the Ithaca area, mostly middle schoolers,” she said.

Grabek linked students in unsafe or unstable housing situations to those who were homeless, identifying that as a spectrum of the longer program.

“One of the girls [a middle school student] I hang out with lives in a part of Ithaca that is definitely rough,” Grabek said. “She lives only five minutes from Boynton Middle School, but she feels very unsafe [walking] to school, because there’s constantly just older men walking around, and she’s scared of being followed.”

Another student takes two TCAT buses to school every day, a public transit system which Grabek noted can be unreliable. When she is late to school, it is for good reason, but Grabek said it is disheartening that teachers claim that her lateness reflects indifference about her education. She said she wrote an email to this student’s teacher, but did not receive a response.

Such experiences have changed how Grabek perceives homelessness altogether. She said that before college, she thought of homelessness as “an adult male issue,” a perception that has since changed to include people of all ages and genders. The biggest revelation, however, is how homelessness can be hidden, she said.

“It’s not necessarily as obvious in a town like Ithaca,” Grabek said, “who’s homeless and who is not, or who is living in a situation that’s dramatically impacted by poverty.”