South Hill Forest Products, a student-run business, preps for the season with smaller staff

The glint of a knife’s blade catches the fluorescent lights overhead. The slick sound of sharp metal sliding out of its sheath rings against the linoleum floor as a group of students watch with rapt attention. Soon, the room is filled with the sound of the knife’s rhythmic scraping — a stark contrast to the quiet Sunday afternoon.

But this isn’t a grizzly scene that’s about to transpire — rather, it’s a group of students voluntarily learning the skills needed to sustain South Hill Forest Products, a student-run business that creates products from the Ithaca College Natural Lands while ensuring the land’s health.

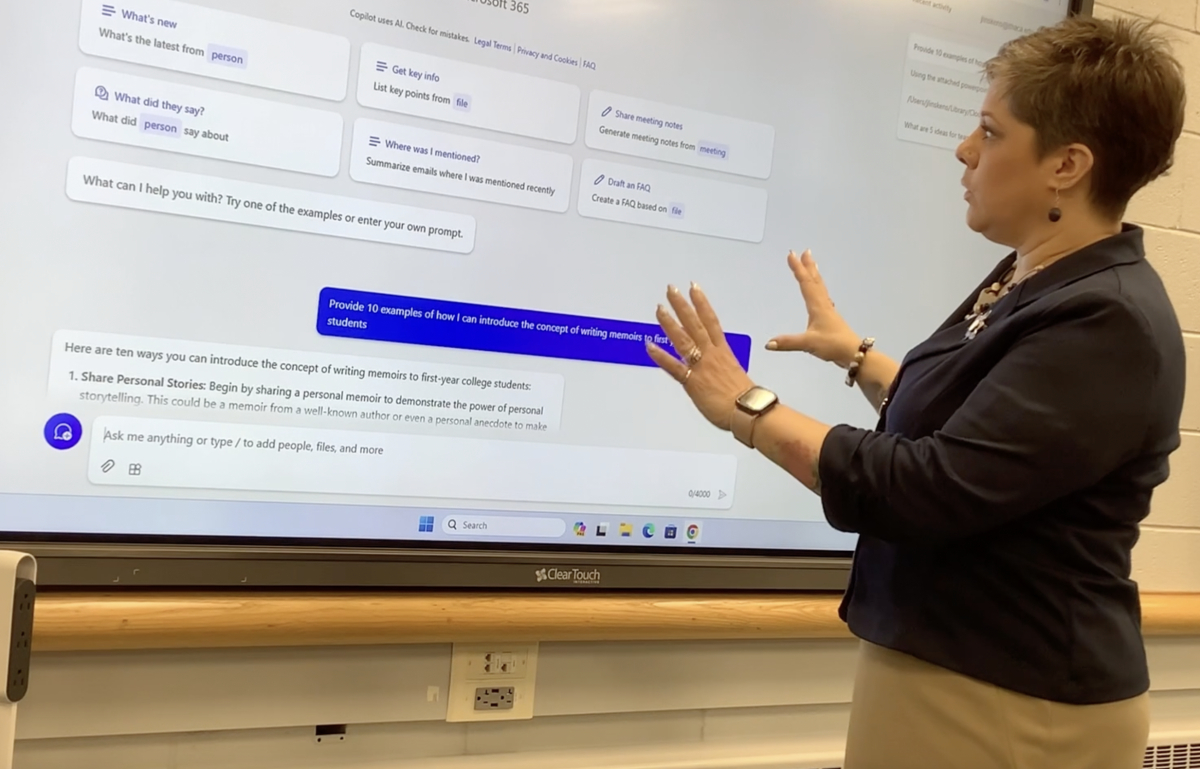

“The important thing is not to stab yourself,” said Jen Skala, a senior environmental studies major at Ithaca College and the leader, who advises the group of aspiring woodsmen.

In the past, South Hill Forest Products has been run each spring by students in Ithaca College’s Non-Timber Forest Products class, often referred to by students as NTFP. But when Jason Hamilton, professor in the Department of Environmental Studies and Sciences and the instructor for NTFP, announced he was going to be on sabbatical this semester, Skala stepped up to be the leader of the group — this time as a club.

“I love doing hands-on things, and this is one of not a ton of classes at [Ithaca College] where everything is very hands-on,” Skala said.

Skala said that she wanted to start the group up again this semester so that the skills learned in class — including how to make and produce both maple and hickory syrup, carve wood, and manage bees — would be passed down to another generation of students. It also doesn’t hurt that NTFP is one of Skala’s favorite classes that she’s taken at Ithaca College.

But there are unique challenges that come with the course — and especially with it now being run as a club. All the challenges and responsibility fall on a smaller group of students who may not have the ability to commit themselves to the class’ 10-hour out-of-class time requirement.

Hamilton, the professor who is usually in charge of the class and of coordinating students, noted that a small group isn’t necessarily an issue, but the commitment of the people involved is crucial.

And even if the trees do know what to do, it’s still hard to predict what the syrup season — from January to about early April — will look like.

“The trick is coordinating the humans involved,” Hamilton said in a phone interview. “The trees know what to do; the people don’t.”

Sam Castonguay, a 2018 IC graduate who took the course during her senior year, is attending club meetings this semester when her work schedule allows. Castonguay explained that it should be above 40 degrees Fahrenheit during the day and below freezing at night for optimal syrup production.

“It’s been really cold so far, so I’m a little concerned,” Castonguay said. “As long as we have those weather conditions, hopefully it’ll be a good year.”

Ideally, students collect barrels upon barrels of sap that can then be boiled for hours on end to remove excess water — leaving behind the sweet, sugary syrup. The students then sell the syrup, along with the other products made over the course of the semester, through South Hill Forest Products’ annual open house. Any remaining products can be purchased online at South Hill Forest Products’ website.

Regardless of how the weather unfolds during the syrup season, the course offers lessons in something greater than syrup or honey — resilience.

“There’s a lot of responsibility on the students, so all the success is on us,” Skala said. “The challenges are up to us to overcome, and if we don’t meet those challenges, we have to deal with it. We learn and we grow, and it’s a wonderful learning experience.”