On the second floor of Uris Hall, an academic building located on Cornell University’s campus, lives a typical, glass display case. Inside lies not prestigious awards or ordinary memorabilia, but something much more extraordinary — eight jars of real, preserved human brains.

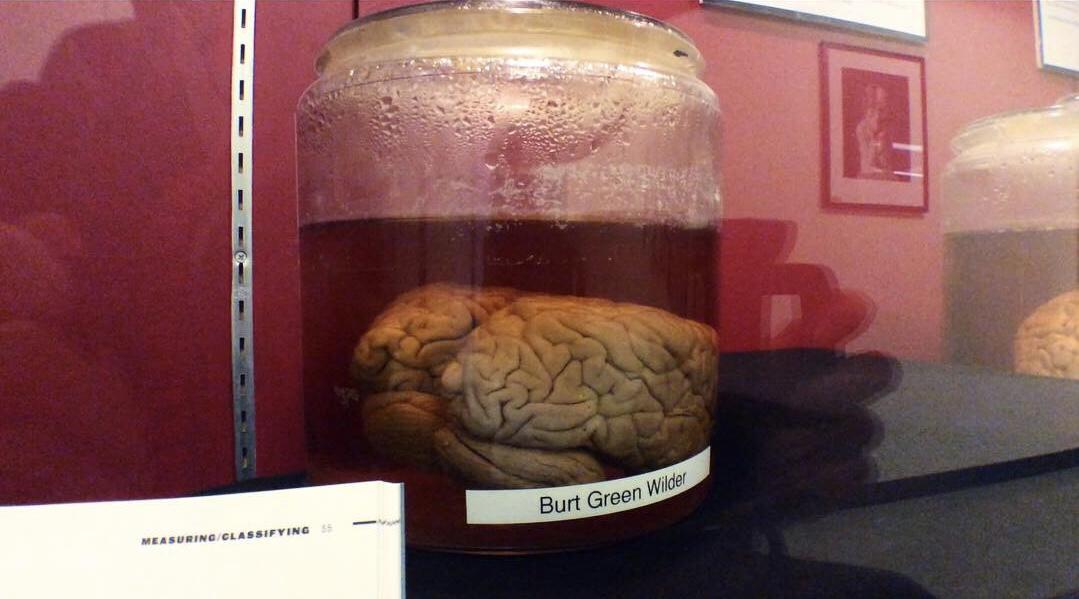

Perhaps more fascinating than the brains themselves, is the history behind them. The collection has been around since the turn of the 19th century, and was the brainchild of Cornell faculty member Burt Green Wilder. Wilder started the project to understand more about the capacities of human knowledge — among other, more controversial topics.

“At the time, there were a lot of beliefs about brain capacity and who had it, and who should be teaching here, for example,” said Cornell Psychology Professor Timothy J. DeVoogd, who is currently in charge of maintaining the collection. “There were ideas that the reason the faculty were mostly males of European descent, was because they had special gifts in learning academic material and making new discoveries. Cornell faculty members started the collection to check out the idea.”

So Wilder and his living colleagues began collecting the brains of the deceased. Hundreds of brains came from Cornell faculty members, but also from ordinary community members — of all races and ethnicities, and of both sexes. What they found, was that there was no discernible difference in the structure, appearance, or size of the brain between males from any ethnic background. They were also thrilled to discovered that on average, the brains of human males were somewhat bigger than the brains of human females.

But, according to DeVoogd, “…the people who were thoughtful about this came to realize that the real measure of brain capacity is not simple size — cows, whales, elephants have big brains — but size in respect to body size. It’s typical in humans, that males have larger bodies than females, and so if you construct the ratio — the ratio is actually slightly larger for human females, than for human males.”

Wilder ended the study with no evidence to prove any special capabilities of white, European males. But the historical significance of what’s now known as the Wilder Brain Collection remains, and today it contains around a few dozen specimens, most of which are stored away in a basement on campus. The case on display in Uris Hall includes the brain of Wilder himself, in addition to those of some other notable donors.

One of these extraordinary locals was Edward Rulloff (born John Edward Howard Ruloffson). A famous 19th century murderer, Rulloff is suspected of brutally murdering his missing wife with chloroform and a knife, as well as smothering his infant daughter, before sinking their bodies in Cayuga Lake. While this rumor has never been proven (and no bodies have ever been found), Rulloff was convicted of murdering a Binghamton store clerk in the 1870s. The evidence? Rulloff had been missing two of his toes, and a shoe at the crime scene had matching indents indicating the toes’ absence. The self-proclaimed genius and distinguished linguist, coincidentally enough, had a brain 30% larger than average.

The collection also includes the brain of Cornell faculty member Helen Hamilton Gardener. A lifelong suffragette and feminist, she was appointed by Woodrow Wilson in 1920 to the U.S. Civil Service Commission — the highest federal position occupied by a woman at that time. She also spent her whole adulthood gathering research to prove that no differences could be found between brains based on gender.

“[She] had to fight to get a faculty position, and was really brilliant,” said DeVoogd. “I suspect that she wanted her brain there to show that there was no meaningful, discernible difference between the brain of a woman and the brain of a man.”

Today, no additional brains are currently being accepted, and the collection is mostly used for display and demonstration.

“Now, it’s of historical importance,” said DeVoogd. “And I encourage anyone who’s interested, in coming out to take a look at this remarkable display of human history.”