“When you look at it, you might say that people put us out here because they didn’t want to see us,” he said.

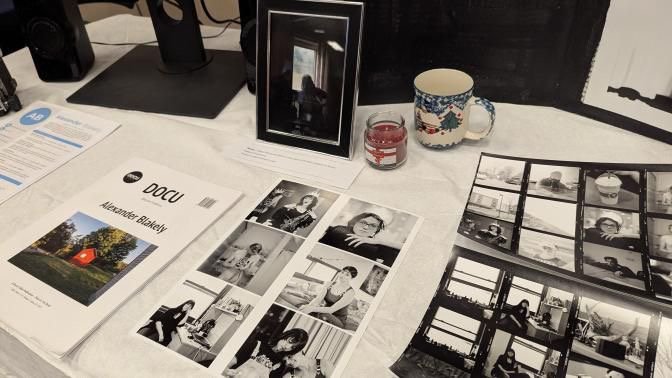

McKinley’s documentary, which he financed through online fundraisers, is a personal account of his experiences with incarceration and police brutality, and has been screening at film festivals nationwide.

“What I did was like a dissertation for my PhD, this movie, and I’m saying ‘Yo, listen, you give anybody that chance, they can do what I just did,’” he said. “You can’t have these hypothesis or thesis if you’re not living amongst them and feeling it.”

The experiences of the communities McKinley chronicles in the film offer a window into the realities of sentencing and policing disparities in poor communities of color. 37.5 percent of the United States prison population is black, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. But only 13.2 percent of the country’s population is black, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

McKinley’s father was killed by a police officer when he was 14-years-old, and he has been beaten by police twice himself. But the pattern of racial injustice he experienced began long before that.

“There were things that I got accused of,” he said. “When I went to high school the teachers were quick to kick you out. I was kicked out of school every year in high school and I had to go to summer school. I was smart though. I was really smart.”

After multiple arrests, a struggle with drug addiction, and his eventual incarceration, McKinley found his status as a convicted felon was making it impossible to turn his life around. Eventually he ended up homeless in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Wanting a way to speak out about his experiences, McKinley went to the community television station, where he learned how to film and edit. He began to develop his filmmaking ability as a method of speaking out against the injustices he had been subjected to.

The personal narrative of “The Throwaways” has a deeper impact on viewers than a film looking at the same subject from a more technical viewpoint, co-director Bhawin Suchak said.

“Instead of giving you a lot of statistics and data and theoretical frameworks we’re showing you a person’s story––a really raw, real story,” Suchak said.

People like Ira are helping to bring an insider’s perspective to a problem often presented in such unfathomable statistical terms that the human reality of being such a statistic isn’t fully understood.

“Artists doing what Ira has done is very important [for the national discussion],” Lou Downey, a spokesperson for the Stop Mass Incarceration Network who has been on the ground in Ferguson since the day following Michael Brown’s death, said. “Both bringing their firsthand experience and also themselves trying to put it in the broader context of what it means for communities and people.”

Rafael Aponte, a farmer at Rocky Acres Community Farm in Freeville N.Y., who attended the Cinemapolis screening, sees the connection between the work that he does, and the work that people like Ira do.

“His story and his narrative resonated with me,” Aponte said. “It’s just really shining a light to marginalized communities that haven’t had a fair shake at what’s going on.”

Aponte and McKinley met after the Cinemapolis screening, and McKinley immediately made it his mission to help connect Aponte to other like-minded farmers that he has met through his activism. He even made a trip out to Aponte’s farm before heading out of town for the next showing of The Throwaways.

McKinley believes that the solution to these deeply entrenched problems of racial injustice must come from the grassroots, and that community food efforts can serve as the primary vehicle to harness the collective potential of marginalized communities. He is currently living in Corning, N.Y. and has been learning how to grow his own food. He is already hard at work on another film, titled “Outta the Muck.”